The Great Frog

Text: Zack Stiling

Somewhere in East London, lost among the crowded grid of Victorian terraced housing and forgotten warehouses, an earnest craftsman hunches over his workbench with carving tools and a steady hand, slaving devoutly over the empty gaze of Death’s head, pausing from time to time only to bring forth new life from old iron in a Mephistophelean burst of smoke and thunder. The temple is that of The Great Frog, its high priest Reino Lehtonen-Riley.

The Lehtonen-Riley family have been humble servants to The Great Frog since 1972, when Reino’s mother Carol Lehtonen and father Paterson Riley answered their calling to bring rock ‘n’ roll to Carnaby Street by selling heavy-metal jewellery, in particular the trademark skull rings, cast in British hallmarked 925 sterling silver. Despite building up a following among the heavy metal and biker subcultures, the business wasn’t the international success it is today when Reino took the mantle in 2006.

“It had a great story behind it but for various reasons it wasn’t making enough money. My dad doggedly stuck at it and refused to close the doors, but he had to borrow all the time and was always just off paying the latest loan, so I didn’t want anything to do with it. Although I liked the engineering and practical side of things, jewellery was his passion, not mine.

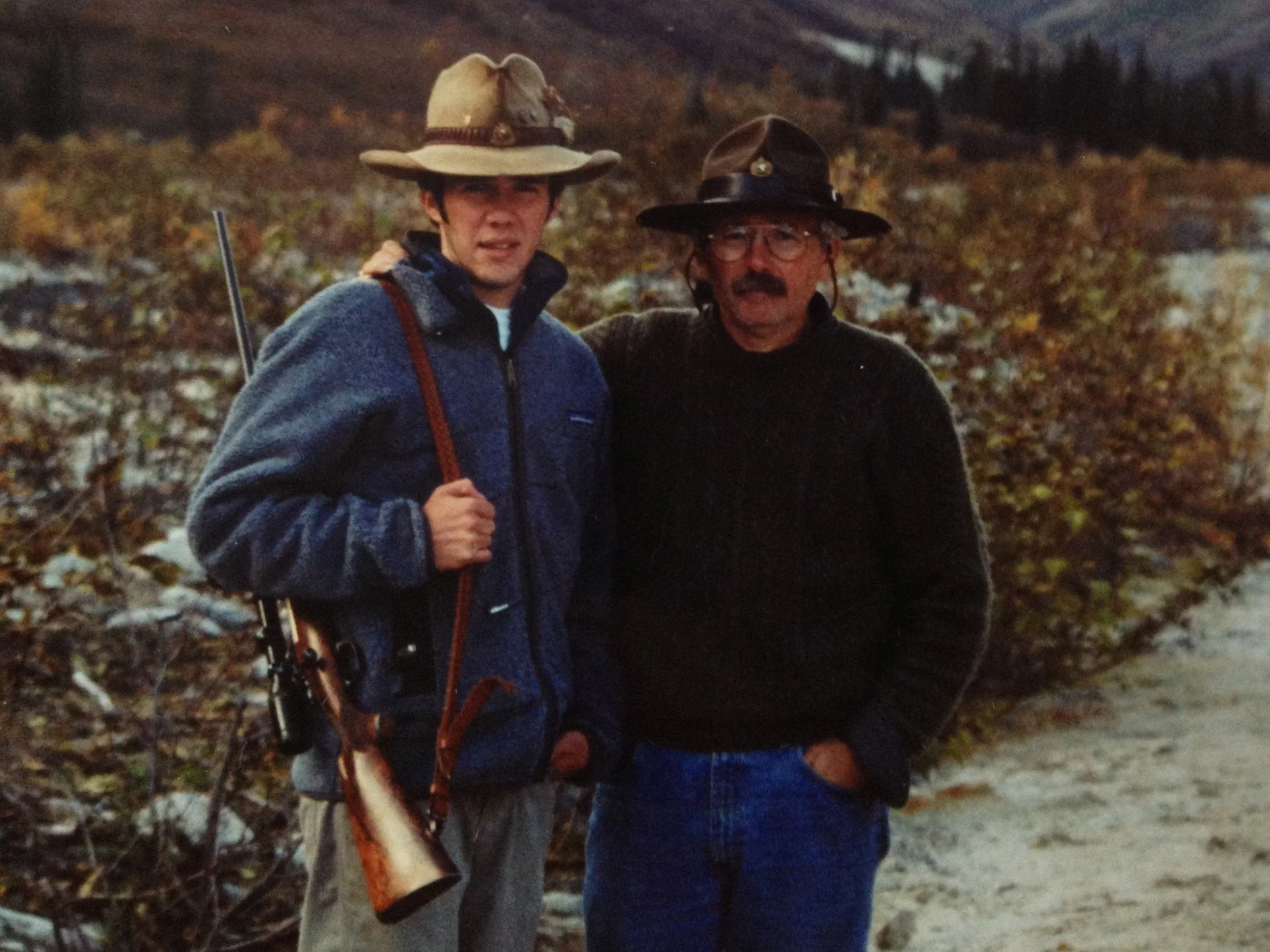

“My parents weren’t conventional. Their friends were all freaks and weirdos with long hair, cowboy boots and leather jackets, they had members of bike clubs turning up to smoke dope and jam in the basement, so my teenage rebellion was being preppy, with chinos and polo shirts. I wanted to go into a career in automotive design, so I went to university to study product design engineering. I wanted to be successful and make money, not to be always scraping the barrel to pay rent.

“I went to New Zealand to live with family and later ended up in Australia, where I worked for Armani. With my last 30 quid, I printed loads of CVs and carpet-bombed Sydney with them, going to every shop – McDonald’s, Burger King and all the rest. Only Armani called me back, so I found myself in retail, pinning people up for alterations.”

While the family passion for jewellery hadn’t yet become manifest in Reino, the seeds had been sown in his childhood. “We had three shops when I was a kid, in Wimbledon and on Ganton Street and Carnaby Street, which were all family-run by aunties, uncles and friends. Each was a workshop with a house, vertically integrated. My playground was going down to the workshop and picking up the trade.”

Armed with a knowledge of branding picked up from Armani, the prodigal son turned homeward to revive the flagging business. “We worked out how to make The Great Frog a brand, cherry-picking the best bits and hiding the shit, like in the ’90s when we weren’t very cool and imported a lot of foreign goods.”

The Great Frog story begins with Paterson Riley’s days as a comic-book lover, his favourite being The Phantom, whose trademark was an ancient skull ring that left a deep impression on every criminal the Phantom struck. “You could send off for your own skull ring by snail mail, which my dad did in order to become all-powerful and defeat his enemies with a single blow. Instead, he waited for ages just for some cheap, plastic skull.

“He was a menswear buyer when he came over from New Zealand and started working in suiting at Harrods, but he wanted to be a rock ‘n’ roll star like Buddy Holly. He hung out on Carnaby Street in the ’60s, putting up posters with Neil Peart from Rush trying to promote themselves. After learning to repair jewellery, he learnt how make it, started selling a few trinkets and then set up The Great Frog. Black, Gothic skulls didn’t exist anywhere in the technicolour Swinging Sixties, so the emerging metal bands had to use him for their iconography. Some people came and stood outside with holy water and crosses, thinking they were Satanists.

“Everything was done then by handshakes. ‘If you make me this ring for me for free, you can make copies of it and sell them,’ and that was how it worked. They were all small bands then, they never expected to be super-groups. The Great Frog’s current range includes rings designed in collaboration with Motörhead, Iron Maiden, Judas Priest, Slayer and Ghost. “They all had a big input on the designs because they’ve come from nothing and they’re proud of their life’s work. I loved the fantasy art on metal albums and would trace the outlines as a kid, now it’s great to be working with the bands.”

As well as overseeing the business, Reino operates as a wax carver in his East London workshop, creating new designs for the TGF range. He works with jewellery wax – like candle wax but harder – and a couple of hand-made tools. “I’ve got a sketchbook full of ideas and designs. Something gives you an idea then you get an obsession and start doing loads of sketches.” Once Reino has refined the miniature sculptures and likes the shape, he sends them to be cast, which his dad and uncle used to do themselves, but the practice was too expensive for Reino to continue.

In lost-wax casting, various wax shapes are hung from the branches of a ‘tree’ inside a cylindrical flask with a rubber base. Investment, a mixture of silica sand and plaster, is poured in and allowed to set before it goes into a kiln to be heated and the wax burned out in a process that has changed little since Roman times. This leaves a hollow cavity in the investment into which molten silver or gold is poured. It hardens quickly, then is removed, polished and sanded. By placing the master in a frame with layers of rubber over it, heating it and vulcanising, a mould is created into which wax can be injected, allowing for copies to be manufactured ad infinitum.

Today, righteous chops are as much a part of TGF culture as heavy metal, a link that was cemented when it collaborated with the pioneering DicE magazine to host the Assembly Chopper Show in London in 2017 and 2018. “The motorcycle side of things is just me trying to shoehorn my personal passion into the business. I inherited it from my mum, who rode a 650 Triumph all over Europe in the ’60s. My dad wasn’t keen because a lot of his motorcycling friends had been killed or injured but, when they separated, I cajoled my mum into buying me a moped! Plus, the market for skull rings in the ’80s was mainly bikers. We traded at the Bulldog Bash, which I went to as a kid, and I was obsessed with BMX and anything with wheels. Early Back Street Heroes has a lot to answer for. Luckily, as it’s my company, I can get away with shoehorning my own interests into it. The best thing is that there’s no one telling you what to do… although the worst thing is also that there’s no one telling you what to do. I’ve got so many interests, I’m always excited by new stuff. It would be boring if you were doing the same thing forever, like a factory production line.

“Everything that’s happened to me has been the result of bikes. Dean Micetich of DicE is very charismatic and really funny. I never thought I’d be able to have a nice bike like a Harley and when DicE came out I was in awe. My then-girlfriend got me a subscription and I was seeing all these amazing bikes from the States. She arranged the subscription over e-mail and Dean responded saying ‘Wait – that’s not The Great Frog, is it? I’ve got one of your rings.’ I thought, ‘Wow! They know who I am!’

“I visited them in LA expecting to be received at some fancy DicE Towers but they were just a bunch of cool, laid-back dudes. I’d never ridden a Harley at the time. There were very few of them over here and those who were really into the lifestyle didn’t have the money to buy them. It’s still a small scene but there’s a real brotherhood camaraderie all over Europe, Japan and the States. From one person you get to know another, or you’ll stop to admire a bike in the street, then the owner appears and before you know it, you’re drinking beers in their garage, even though you might not speak the same language. Dean, Matt Davis and I opened TriCo in LA. They needed to expand the DicE office and I wanted to break into the States. I came up with the name TriCo obviously because it was three companies – DicE, The Great Frog and Dixie Clothing. Then we opened our own branch of The Great Frog in LA.”

Only a small corner of Reino’s workshop is required for wax carving. The remaining space is a miniature motorcycle museum, mainly traditional choppers, in various states of assembly. The building itself is as interesting and characterful as everything contained with it, having originally been built in the 19th century as a dépôt for cleaning and repairing hackney carriages, complete with sloping floor for ease of sweeping away the accumulated filth. “I lived in a tiny studio flat nearby and was walking to the Underground one day when I saw this skip full of old equipment outside. I come from a long line of skip-divers and had a rummage when I was interrupted by some workers. I ended up buying some cast iron tables from them, which I turned into jewellery cases. It had all come from a printing firm which had just lost out to the digital age. The building was going to be vacant, so I harassed them for it and eventually they let me have it. An evangelical African church uses the top floor, so the place is like a metaphor for heaven and hell, but we’re much less sinister down here!”

Another unconventional hobby of Reino’s is his collection of ancient human skulls. “I just grew up around real skulls which my dad had for reference and didn’t find them unusual. I only started to think later about mortality and the weirdness of putting your hand in a brain cavity. You anthropomorphise them and think about how they lived and died but there’s also an aesthetic quality. They’re all different and you can identify race and gender. I see every unique detail. I started noticing them in antiques places and they were so powerful, I’d buy them whenever I saw them. I found one in Amsterdam that was distinctly Germanic with its angular brow. You can see where they’ve decayed or been smashed and I started performing repairs using silver. Shortly afterwards, I smashed my own skull in a wakeboarding accident and now have a titanium cheekbone…”

Motivated by an enthusiasm for so many facets of life, Reino has built up The Great Frog so that it now operates shops in Soho, Shoreditch, New York, Los Angeles, New Orleans and Tokyo, with 30 people currently employed by the two London shops. After nearly five decades of forging argent idols at the altar of The Great Frog, the all-seeing, all-knowing amphibian clearly wishes them many more years of success.