La Dolce Vita and the Triumph TR3A

The fully restored TR3 that appeared in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960). All photography courtesy of Racing Colors, Rimini.

Text: Roland Novak

“Marcello, come here. Hurry up!” “Si, Sylvia, vengo anch’io. Vengo anch’io.”

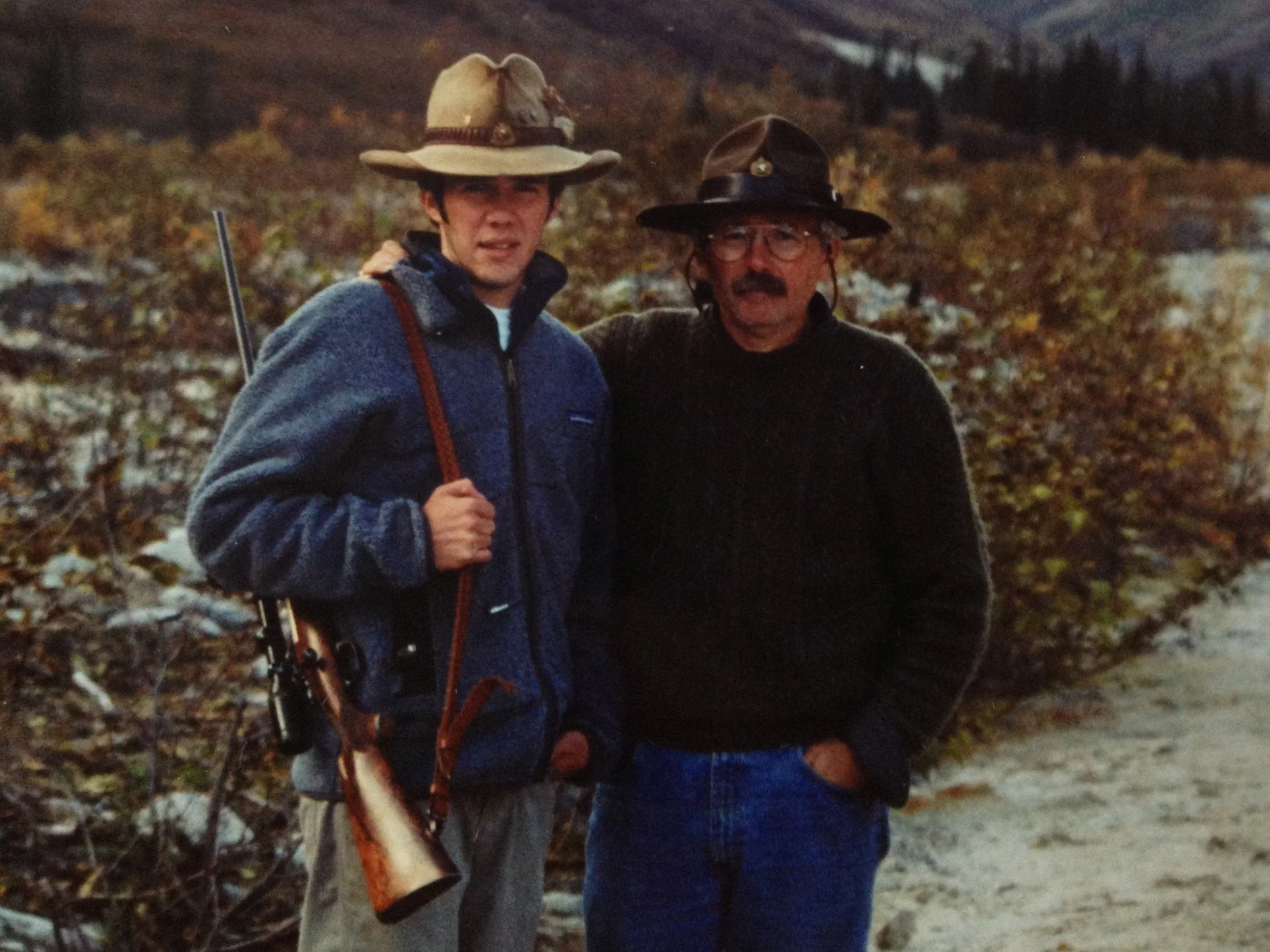

In these early morning hours of a rather cold March in 1959, the baroque beauty of the Fontana di Trevi is about to be overshadowed by exuberant blonde Sylvia (Anita Ekberg) in her long black dress. The scene in which Sylvia’s call for Marcello (Marcello Mastroianni) to enter the freezing water with her, lasts just a minute, then the cascading flow suddenly stops. This movie moment remains part of the collective memory for fans of Italian cinema and is still seen as emblematic of the ‘bella vita’ of the 1950s. The sequence is one of the many vignettes in the intricate storyline of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita. The complex structure of this two and a half hour film can be subdivided in seven episodes with a separate introductory chapter and an epilogue. I recommend the work of Peter Bondanella “The Cinema of Federico Fellini” (1992, Princeton University Press) for further investigations on the symbolism underlying “La Dolce Vita”. What’s confusing on first sight, is the sometimes, disruptive nature of the consecutive episodes. Although each segment features the unifying figure of Marcello Rubini, a handsome and ambitious young journalist played by Mastroianni. But here we place all normal film criticism to one side and focus on the dark Triumph TR3A, one of the few imported directly from the UK in 1958. Registered for the first time in Rome on July 15, 1958 (in white), it was one of the first ‘spider inglese’ in Italy, bought for 1.9 million Lire by Armando Berni, the nephew of the Roman ‘Re delle Fettuccine’ (king of pasta) Alfredo Lelio. As a side note, the average salary in 1958 consisted of 45,000 Lire, just to get an idea of the real value of this kind of commodity in Italy in 1958. It seems that within a few months the car had been spotted by Fellini and purchased by Riama Film – a production company involved in La Dolce Vita. By the time it appeared in the film it was painted black. As Fellini himself recounts, between Marcello Mastroianni and him, it was a sort of constant challenge for who owned the fanciest car: “Marcello comprava la Jaguar e io la Triumph, lui la Jaguar e io la Porsche.” After the completion of La Dolce Vita, the TR3 was sold in the following years into different collections of historical cars and eventually returned to its original colour. During this period the link to the movie was lost and, when the car was purchased in 2016 for 30,000 Euro by Filippo Berselli, himself a collector of historic cars, its full backstory was unknown. As with many passionate collectors Mr. Berselli had developed a sixth sense for an old car with an interesting provenance. After a short inspection he found some further information on the real history of his recent purchase. The black number plate was indicative of this being a car imported directly into Italy from the UK and not arriving via the USA, as with most foreign cars in the 1950s. Berselli managed to get hold of the original UK production and export documents regarding this ‘wide mouth’ (the nickname refers to the enlarged grille on the front) Triumph TR3. The new owner then commissioned Racing Color di Pompilio Fabrizio near Rimini for a sympathetic restoration in which the TR3 became black again, got new electrics installed and was re-trimmed in the original red upholstery.

Back in 1959 the Fellinian Triumph, with Marcello Mastroianni in the driver’s seat, represented one of the few constants in La Dolce Vita. The other recurring theme can be identified with the modernist scenery of the Via Veneto that, like the British sports car, was emblematic of Italy’s optimistic and opulent post-war boom. Such good times (La Dolce Vita) revealed vast splits in Italian society in which the political left established a new power-base and the intellectual classes (represented by Marcello’s friend Steiner, in the film) feared populism would corrupt Italian culture. Typical of Fellini, his knack was to bring together a cast of characters that represented the full spectrum of Italian post-war society: thinkers, aristocrats, models and the petit bourgeois on-the-make, were staples in his language of film. Thus, the café-society of the Via Venato became the backdrop for this milieu in which the hedonistic gossip journalist Marcello Rubini (Mastroianni) and Paparazzo, his photographer and sidekick, plied their squalid trade. Their chosen mode of transport being that iconic TR3 and the ubiquitous Vespa – bear in mind that the GS 160 came out the same year as the film. But the Cafés and restaurants, like the Strega, Harry’s Bar or the Doney, were already overcrowded by the particularly fashionable and popular, so Federico Fellini had to rebuild this sidewalk with his unique eye for detail at Cinecittà’s Studio 5. The only difference between production designer Pietro Gherardi’s reconstruction and the original venue was, that the real Via Veneto was slightly uphill, while the Studio’s setting was level. But details of this kind caught the cinematic spirit professed by Fellini, his fantastical realism that followed his admonition, ‘cinema shouldn’t recreate reality, it should summon its own reality.’